|

Dr. Idriz Merdžanić, a Bosnian doctor who treated victims of the Trnopolje Camp, speaking about how he tried to have two injured children evacuated from the northwestern Bosnian town of Kozarac. He testified on 10 and 11 September 2002 in the case against Milomir Stakić.

Read his story and testimony

“ It took some persuasion to convince my Serb neighbour with whom I had lived my whole life that I was suddenly his enemy and that I was to be killed. ”

In the night of 29 and 30 April 1992, Serb forces took over the city of Prijedor. Dr. Merdžanić said that they stormed all the important buildings, including the municipal building, the courts and the health center in Prijedor, and set up checkpoints, where he was stopped while on his way to work.

On 24 May 1992 at around noon, Serb forces attacked the town of Kozarac without giving women, children and elderly an opportunity to leave beforehand. At the time, Dr. Merdžanić was working in the town's medical clinic. In the two days that the attack lasted, he treated a number of civilians injured by the shelling. Among them were two children: “There was a little girl there,” he said, “whose lower legs, both of them were completely shattered. She was dying.” Dr. Merdžanić tried to have the two children evacuated, but was denied permission. “Let all of you balija” – derogatory for Muslims – “die there,” he was told. “We’ll kill you anyway.”

Photograph of a Trnopolje detainee

(Prosecution Exhibit S321-7 from the Stakić case)

After Kozarac surrendered on 26 May 1992, three Serb soldiers entered the clinic and captured Dr. Merdžanić and his colleagues. One of them searched the building, yelling that everyone was to be killed. Another left the clinic and returned with a green military truck with Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) insignia onto which Dr. Merdžanić and his colleagues loaded all the medical supplies they had, which he never saw again.

While the Serb soldiers were taking them to the center of Kozarac, and then onward to the Trnopolje camp, Dr. Merdžanić saw soldiers breaking into damaged houses and looting them.

When they arrived at the Trnopolje camp, Dr. Merdžanić and his colleagues were taken to the clinic. At first, they thought that since they were civilians, they would be released after an identification check. After several days, they realized that they would not leave. During that time, new busloads of people kept arriving. “The camp was being filled to capacity,” said Dr. Merdžanić. The men would be separated from the women, with most of the men being held in the school building, while the women and children were put in the community center.

The day after they arrived, as darkness fell, Dr. Merdžanić said that “a very loud horrible shooting began.” He and his colleagues threw themselves on the floor, not knowing what was happening. “It was only the next day that we found out they were just shooting bullets into the air for fun.”

“ Mr. Stakić (…) is a physician just like I am, and he made decisions concerning the camps. He knew that we were there. He knew about dozens of doctors, physicians being taken to Omarska and killed. Why? What for? Why were those people killed? ”

Dr. Merdžanić described for the court the conditions in the camp. He and his colleagues, like everyone else at the camp, slept on the floor. Camp authorities provided no food. Initially, the local population brought some food to the camp. Then the Serbian Red Cross arranged for milk to be brought for the children and for the detainees to pay for bread. Later, the camp guards escorted the detainees to forage for food. Dr. Merdžanić said that he and his colleagues received food brought by local Serbs who used to be his patients and sometimes came to the clinic for examination. The International Red Cross organised food delivery after they visited the camp on 15 August 1992.

There was some water in the camp when Dr. Merdžanić and his colleagues arrived, but as it was yellowish and obviously not very clean, they did not use it. Several days later, the camp ran out of water completely. Dr. Merdžanić said that people could not wash, or change their clothes. There were toilets in the school building, but they soon filled up. They did not have any toilets at the clinic, but organized septic pits to be dug out near the school building.

Guards were posted around the Trnopolje camp, and it was surrounded by a fence, which Dr. Merdžanić said one could easily jump over. “But apart from the checkpoints and the guards, even if only a simple line had been drawn on the ground, nobody would dare cross that line.” Dr. Merdžanić said there were machine guns in various locations, and they were pointed towards the camp.

In the months that Dr. Merdžanić was at the camp, he treated women who had been raped. From the clinic window, Dr. Merdžanić and his colleagues could see men go into the women's sleeping quarters at night, flash their lights at the women they liked and take them out. Some of the women later came to the clinic to ask for help. Dr. Merdžanić succeeded in having a number of them sent to the gynaecological ward in Prijedor to investigate their allegations. He later found out that they had indeed been raped.

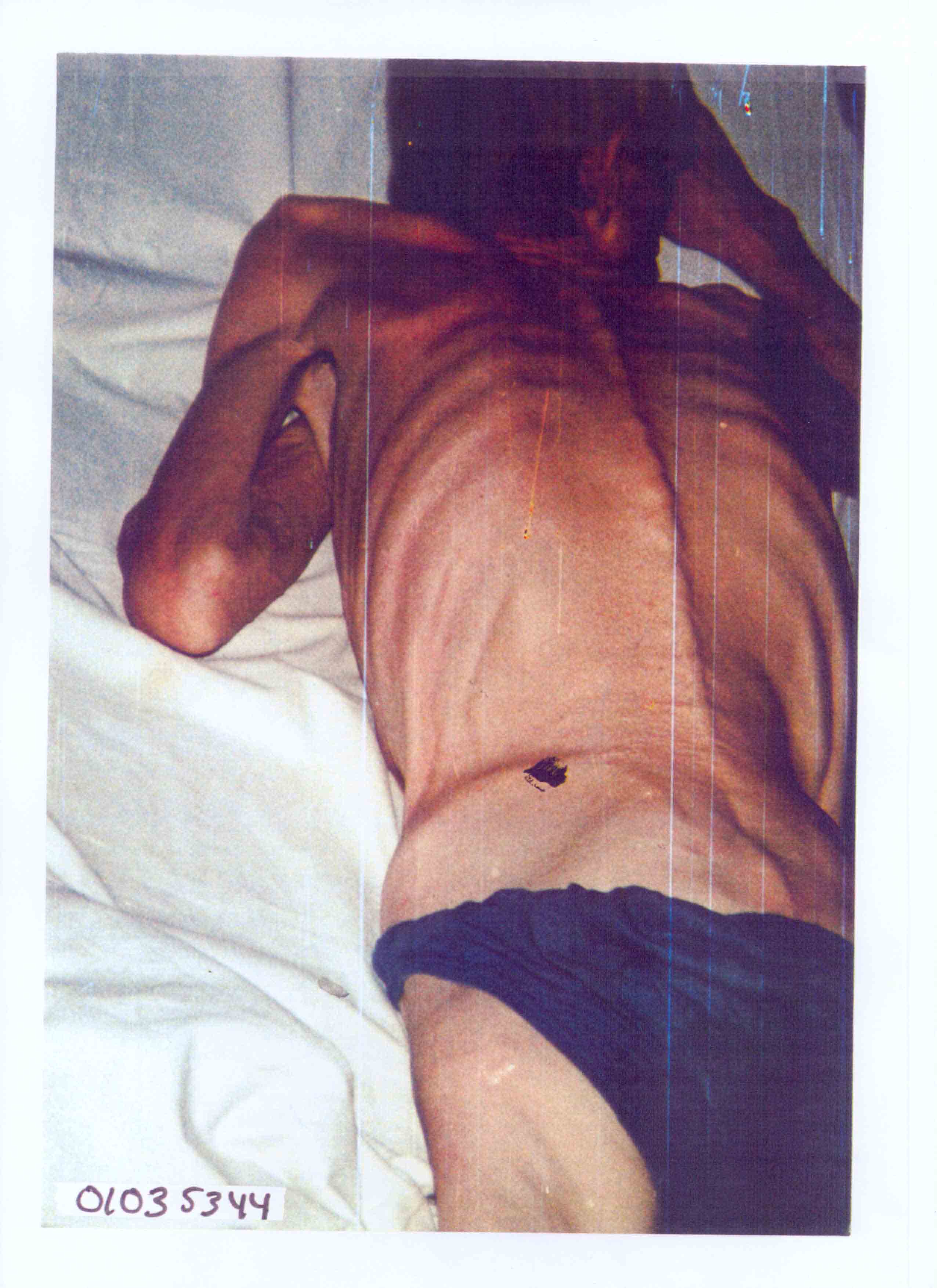

Photograph of a Trnopolje detainee

(Prosecution Exhibit S321-14 from the Stakić case)

Dr. Merdžanić said that the Trnopolje military commander once tried to discipline a rapist. When the rest of the soldiers found out, they got drunk, drove two tanks in front of the main military barracks and gave an ultimatum that the soldier had to be released or they would shoot at their own barracks. The soldier was released.

In June and July 1992, beatings in the camp were very frequent. One of the rooms in the clinic was being used to interrogate and beat male camp detainees. Dr. Merdžanić and his colleagues heard the sounds of people being hit and moaning, and the Serbs verbally abusing their victims. Some of them were brought to the clinic and Dr. Merdžanić and his colleagues dressed their wounds, which he said were normally blunt force trauma or cuts from knives. He said that one inmate had suffered a cut below his knee that severed a nerve. As a result he could not move his foot and always dragged it behind him.

One of Dr. Merdžanić's colleagues had a camera, which they used to photograph the injuries people had sustained so that someday they could prove what happened. In order to minimize the risk to themselves, the clinic staff photographed the injured detainees in secret. When a British television network came to the camp in August 1992, Dr. Merdžanić was able to hand the film over.

Dr. Merdžanić said that the man in this photograph (Exhibit S321-7) is Nedžad Jakupović, who had been brought to the clinic from the room where the beatings took place. His face was bleeding and bruised, and his eyes were so swollen that he could barely see anything. His wrist was fractured and he had wire marks cut into the skin of his arms. The clinic staff were able to photograph him in secret because the man was half conscious.

Dr. Merdžanić said that this photograph (Exhibit S321-14) is of a man who had also been in the room where the beatings took place. Dr. Merdžanić said that he suffered from dysentery, and must have been tortured. He was certain that the man's weightloss was a result of his stay in Trnopolje. He later died.

Dr. Merdžanić said that some 200 men were killed at Trnopolje, while others died because the clinic staff did not have proper medication to give them.

Dr. Merdžanić was one of the last people to leave Trnopolje on 30 September 1992, and eventually ended up in a refugee camp in Karlovac, Croatia. He said that no one could leave the Trnopolje detention camp without signing a certificate relinquishing their property to Serbs. Dr. Merdžanić's property, and that of the majority of Muslims in Prijedor, was destroyed. At the time he testified in 2002, Dr. Merdžanić had not been back to Prijedor since 1992.

When asked by Judge Wolfgang Schomburg to give his opinion on who is responsible for what happened in the Prijedor area in 1992, Dr. Merdžanić said that he believed that Serb politicians used propaganda to convince their people to oppose the Muslims and Croats. “It took some persuasion to convince my Serb neighbour with whom I had lived my whole life that I was suddenly his enemy and that I was to be killed.”

Dr. Merdžanić added: “Why was I put into the camp and then held there for such a long time? What did I do? Can they name at least one thing that I did wrong? Mr. Stakić is here. He’s a physician just like I am, and he made decisions concerning the camps. He knew that we were there. He knew that his colleague Jusuf Pašić, who was facing retirement, had been taken to Omarska and killed there. He knew about dozens of doctors, physicians being taken to Omarska and killed. Why? What for? Why were those people killed? Those people were the Muslim intelligentsia, and they meant something, they were prominent people. Is there an answer to all of this?”

Dr. Idriz Merdžanić testified on 10 and 11 September 2002 in the case against Milomir Stakić, the leading figure in the Prijedor municipal government. The Tribunal convicted Milomir Stakić of crimes committed in Kozarac and the Trnopolje camp, among others, and convicted him to 40 years’ imprisonment.

> Read Dr. Idriz Merdžanić’s full testimony